Millets are one of the oldest farmed cereal grains in the world and are believed to be the first domesticated cereal grain. There is evidence that millets were cultivated in Asia and Africa over 5000 years ago and that they eventually became a staple food worldwide. Millets belong to the grass family and are small, rounded whole grains in shades of red, brown, green, and creamy yellow. According to archaeologists, the cultivation of millets was more common in prehistory than the cultivation of rice!

About Millets

After World War II, corporations and governments wanted to increase the yield and market share of wheat and rice by using an abundant amount of water, fertilizers, and pesticides; they called this “The Green Revolution.” After this, rice production doubled and wheat production tripled. This change dropped the millet share in food grain production from 40% to 20%, leading to some serious agricultural, environmental, and nutritional consequences.

Some believe that due to millets not requiring agro-chemicals and being well adapted to small, diverse farms, governments with ties to agro-chemical corporations and large food companies did not promote it, investing instead in rice and wheat, which require more machinery, hybrid seeds, fertilizers and pesticides to grow. While this view seems harsh on governments, many at the time believed that chemical agriculture would improve yield and increase food security. However, it turns out that this thinking was flawed; in fact, millets are resistant to rot and insects, which means they can be stored for years, making this grain an important staple in areas struggling with food security. Unfortunately, many modern urban consumers consider millets to be “coarse grains,” which were fine for their village ancestors but not “refined” enough for modern tastes. This marked the beginning of the ultimate downfall of millets as a staple grain.

Millets can provide significant benefits to consumers, farmers, and the environment. Consumers benefit from the nutritional value of millets, while farmers can make use of dry land that is not suitable for rice or wheat to grow millets, which will lead to economic benefits for the farmers. Growing millets even benefit the environment since it promotes soil sustainability, conserves water, and does not require many pesticides and fertilizers. In light of these benefits, a lot of effort is being made by many organizations to bring millets back as a staple food for people around the world. In fact, the United Nations General Assembly has declared 2023 as the “International Year of Millets!” After being proposed by India, the idea was supported by over 70 nations in an effort to educate the world about the nutritional and ecological benefits of millets and to encourage governments to facilitate millet production and consumption.

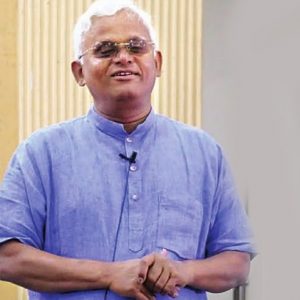

Dr. Khadar Vali is an independent scientist, homeopathic doctor and farmer who is known throughout India as “The Millet Man.” Although there are many varieties of millet grown all over the world that have yet to be identified, Dr. Khadar Vali has identified nine main millet varieties. He has classified these nine millets along with rice and wheat into three-grain categories: “Positive Grains,” “Neutral Grains,” and “Negative Grains.” According to Dr. Khadar Vali, the five millets in the “Positive Grains” category (Browntop Millet, Barnyard Millet, Little Millet, Kodo Millet, and Foxtail Millet) have properties that can cure health issues within 6 months to 2 years, if eaten regularly. However, as with any dietary change, each person’s body may respond differently.

Dr. Khadar Vali further suggests that the four millets in the “Neutral Grains” category (Finger Millet, Proso Millet, Pearl Millet, and Sorghum Millet) can prevent health issues and maintain good health. Finally, rice and wheat fall into the “Negative Grains” category and are to be avoided according to Dr Khadar Vali, as these two grains increase the possibility of developing health issues.